The intersection between my various areas of interest never ceases to amaze me. I'm constantly finding connections between areas of interest that I would never have thought had any connection at all.

For instance, I'm very interested in "The Arts", particularly the writing arts, and as a part of that interest I've been following some of the ongoing discussions regarding copyright law over the past ten years. I'm also interested in French colonial history in North America. You wouldn't think there'd be much overlap between those subjects, would you? Neither did I, until this morning when, stuck on a couch with my box of kleenex, I caught up on my NY Times reading.

Reading the book section, I happened upon a long and thought provoking piece by Daniel Smith on

Lewis Hyde, the poet, essayist, translator and thinker-about-the-arts. Although I knew the name, Lewis Hyde, I knew little about him and had never read Hyde's seminal 1983 book,

The Gift. Hyde is working on a new book that will apparently discuss the ongoing issues with respect to copyright.

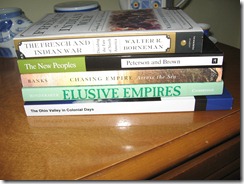

After finishing the piece, I decided that I needed to read

The Gift. Smith's brief statement that Margaret Atwood "keeps a half dozen copies of

The Gift on hand at all times to distribute to artists she thinks will benefit from it" was probably enough to make me think that I should read it. But as Smith described it, I found myself wanting to read it for its own sake and partly because it connected with some of my reading on French colonial history.

The Gift, according to Smith, grew out of Hyde's reading of Marcel Mauss' essay about gift exchange societies.

His [Mauss] essay on gift exchange drew on the work of the seminal turn-of-the-century ethnographers Franz Boas and Bronislaw Malinowski to explore aboriginal societies in which the person of consequence — the man or woman who is deemed worthy of adulation, respect and emulation — is not the one who accumulates the most goods but the one who disperses them. Gift economies, as Mauss defines them, are marked by circulation and connectivity: goods have value only insofar as they are treated as gifts, and gifts can remain gifts only if they are continually given away. This results in a kind of engine of community cohesion, in which objects create social, psychological, emotional and spiritual bonds as they pass from hand to hand.

Hyde found this idea useful in his thinking about why The Arts are valuable in a market based society.

The ideas resonated deeply with Hyde. For nearly a decade he had been struggling to explain — to his family, to nonartist friends, to himself — why he devoted so much of his time and energy to something as nonremunerative as poetry. The literature on gift exchange — tales, for example, of South Sea tribesman circulating shells and necklaces in a slow-moving, broad circle around the Trobriand Islands — gave him the conceptual tool he needed to understand his predicament, which was, he came to believe, the predicament of all artists living “in an age whose values are market values and whose commerce consists almost exclusively in the purchase and sale of commodities.” For centuries people have been speaking of talent and inspiration as gifts; Hyde’s basic argument was that this language must extend to the products of talent and inspiration too. Unlike a commodity, whose value begins to decline the moment it changes hands, an artwork gains in value from the act of being circulated—published, shown, written about, passed from generation to generation — from being, at its core, an offering.

Without reading

The Gift, I can't tell if I agree with Hyde's premise but the idea of the importance of gifts corresponds to my reading about the relations between the colonial French and the Algonquian and Illini tribes of the 17th century Great Lakes region.

One of the most enlightening books I have ever read is Richard White's

The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in The Great Lakes Region 1650-1815. I don't think I'm exaggerating when I say that my entire way of thinking about French colonial life changed after reading this book.

Part of White's book examines the importance of gifts in Algonquian society. The French noted early in their relationship with the Algonquians that the Algonquians held liberality in high regard. Gift giving was a mark of the status and power of the giver and it was also a route to greater status and power. The French noted that sometimes the chief of a tribe had fewer possessions than other members of the tribe because he always gave away what he had.

Gifts were key to every transaction in society. A request had no significance if it was not accompanied by a gift. An agreement was not binding without an exchange of gifts. Marriages involved the giving of gifts. The power to mediate between opposing factions required the ability to present gifts to each side either to seal an agreement or to compensate one side for a loss it had received from the other side. Although the French understood the giving of gifts in the European sense, they had not encountered this volume of exchange of goods in any form other than trade before. They would need to adjust their way of thinking.

White contrasts the hierarchical, highly coercive French society in which the King was at the top, to be obeyed upon pain of death, and the society of the Algonquians. At the top of the French colonial society was the Governor of New France, the representative of the King in North America. The Governor was called

Onontio by the tribes, a Mohawk term meaning

Great Mountain that was probably the literal rendering of the actual name of an early Governor.

White's central premise is this:

Because the French and Algonquians were trading partners and allies, the boundaries of the Algonquian and French worlds melted at the edges and merged. Although identifiable Frenchmen and identifiable Indians continued to exist, whether a particular practice or way of doing things was French or Indian was, after a time, not so clear. This was not because individual Indians became "Frenchified" or because individual Frenchmen went native, although both might occur. Rather, it was because Algonquians who were perfectly comfortable with their status and practices as Indians and Frenchmen, confident in the rightness of French ways, none the less had to deal with people who shared neither their values nor their assumptions about the appropriate way of accomplishing tasks. They had to arrive at some common conception of suitable ways of acting; they had to create ... a middle ground.

White points out that the establishment of what eventually became the middle ground evolved through many steps, beginning with the crude first step in which each side tried to assimilate the other side into its own conceptual order - the French categorizing the Indians as

sauvages with religions that amounted to devil worship and witchcraft and the Indians categorizing the French as

manitous. And because the French were literate and wrote down these first impressions, people on the far side of the Atlantic who had never set foot in North America and perhaps had never met a native American gave these first impressions staying power and influenced how Frenchmen

not on the ground in North America continued to view the native peoples.

The most important thing to remember about French/Algonquian relations was that neither side had the upper hand. Unlike other European powers in the New World, France never sent enough people to gain its ends by force. The French were always outnumbered. They were outnumbered by their Indian allies and they were outnumbered by their enemies - the Iroquois and the Iroquois' English allies. In order to protect themselves from the Iroquois and the English, the French needed the alliance with the Algonquians.

In addition, the French needed the Algonquians because the French economy in the New World was an economy based on trade - the trade of European goods for furs. Not an economy based on exploitation of the land, like the English, or an economy based on exploitation of silver mines, like the Spanish.

The Algonquians, in turn, needed the French. Not, as is commonly thought, for their trade goods. It would be a long time before the Indians were so dependent on European trade goods that they could not live without them. No, they needed the French to be an honest broker between tribes. As the Iroquois and disease pushed the Algonquian and other peoples west of the Great Lakes, they were jumbled together as refugees often are. Their ability to fight against the Iroquois (and the Sioux, against whom they were pushing on their western boundaries) depended on their ability to get along with each other. The French, as outsiders with access to goods that were highly prized presents, allowed them to act as mediators among the warring blocks crammed together along the shores of Lake Michigan and back into what is now Wisconsin. It allowed them to convince the refugee Indian tribes to act, and to help them coordinate the actions, in concert against a common enemy; to stop the bleeding so to speak.

The middle ground depended on the inability of both sides to gain their ends through force. The middle ground grew through the need of people to find a means, other than force, to gain the cooperation or consent of foreigners. To suceed, those who operated on the middle ground had, of necessity, to attempt to understand the world and the reasoning of others and to assimilate enough of that reasoning to put it to their own purposes.

The other important thing to recognize about the French/Algonquian middle ground is that it is based on congruences that did not necessarily derive from a true understanding of the other side. Again, White:

Those operating in the middle ground acted from interests derived from their own culture, but they had to convince people of another culture that some mutual action was fair and legitimate. In attempting such persuasion people quite naturally sought out congruences, either perceived or actual, between the two cultures. The congruences arrived at often seemed -- and indeed were -- results of misunderstandings or accidents. Indeed, to later observers, the interpretations offered by members of one society for the practices of another can appear ludicrous. This, however, does not matter. Any congruence, no matter how tenuous, can be put to work and can take on a life of its own if it is accepted by both sides. Cultural conventions do not have to be true to be effective any more than legal precedents do. They have only to be accepted.

One of the congruences that worked for the French and the Algonquians was the concept of father/child that took hold. For the French, to be thought of as "the Father" played into its feeling of being the person in charge who was to be obeyed which it saw as the natural order, despite the greater number of Indians.

For the Algonquians, the term "father" had a different connotation. Fathers weren't to be obeyed, they had no coercive power. But as the person with the ability to provide, Fathers were

expected and obligated to provide. And as the person with more access to goods necessary for presents, fathers were expected to try to convince their children to get along. The fact that the French had access to goods that made wonderful gifts gave the French the

obligation from the point of view the Algonquians, to provide those gifts and to mediate. There was no reciprocal obligation on the part of the Algonquians to obey. On this misunderstanding was the entire long lasting father/child relationship between the French and the Indians born.

One of the biggest hurdles that the French and the Indians had to cross was to understand how coercion did or did not play a part in the other society.

... Algonquian village leaders, unlike Onontio and his French officials, were not rulers. The French equated leadership with political power, and power of coercion. Leaders commanded; followers obeyed. But what distinguished most Algonquian politics from European politis was the absence of coercion. ... As Chigabe, a Salteur chief, and probably a lineage head of one of the proto-Ojibwe bands of Lake Superior told Governor Frontenac: "Father: It is not the same with us as with you. When you command, all the French obey and go to war. But I shall not be heeded and obeyed by my nation in a like manner. Therefore, I cannot answer except for myself and for those immediately allied or related to me.

If an Algonquian leader could not coerce, he could convince. And presents were a way to convince. By giving Algonquian leaders gifts that could in turn be passed along to others, the French were giving the Algonquian leaders the ability to convince their people to go along with plans that the French desired.

Keeping all of this in mind, White looks at the fur trade which is normally looked at from the French point of view with most exchanges being a form of commerce and other occasional exchanges being a form of gift giving.

It is just possible, however, to create a counter image in which the fur trade proper is merely an arbitrary selection from a fuller and quite coherent spectrum of exchange that was embedded in particular social relations. The fur trade was a constantly changing compromise, a conduit, between two local models of exchange -- the French and the Algonquian.

Both sides had models of equitable exchange. ... The Algonquian model proceeded from a different logic [than the French market model] and can be distinguished from the French on a series of important points. First of all, the goal of the transaction was not necessarily profit - securing the maximum material advantage. It was ... to to satisfy ... the needs of each party. Second, the relation of the buyer and the seller was not incidental to the transaction; it was critical. If none existed, one had to be established. Third, the need of the buyer was an important element in the logic of the exchange, but it exerted an influence opposite to that it exerted in the French model. The greater the need ... the greater the claim of the buyer on the seller.

In other words, the Algonquians only "traded" with those with whom they had a personal relationship (family, either real or symbolic) and the exchanges took the form of providing for the needs of the other person and if one side had greater need, the person with the greater means was obligated to try to meet their needs.

If the French wanted to trade with the Algonquians they had to understand at some level that exchanges of goods could not always be for mercenary reasons. At the same time, although the Algonquians had their own reasons for exchange of goods, by trading with the French at any level they had, without a doubt, entered into a global world market in which the furs they traded were eventually distributed all over Europe in the form of finished goods such as hats. And thus, the market system of Europe did impact their lives, as gluts of furs would cause Europe to send over fewer trade goods that could be used for presents to assist in mediation between the tribes. But the market never dominated the fur trade system because the French, especially in the 18th century as England became more and more powerful and her reach grew further, were fully aware that the requirements of the military alliance would necessitate the taking of actions that the market would not tolerate. As White says:

But precisely because the fur trade could not be completely separated from the .... relations of political and military alliance, a straightforward domination of the local Algonquian village by the market never emerged. Instead, a system of exchange developed that was notably different from earlier Algonquian models; it was a system influenced by, and yet buffered from, the market. The French-Algonquian alliance was the buffer. To allow profit alone to govern the fur trade threatened the alliance, and when necessary, French officals subordinated the fur trade to the demands of the alliance.

In other words, when the alliance demanded it, the French would countenance "trade" at unprofitable levels to keep the allies happy; they would act in the Algonquian mode as a giver of gifts that were needed because allies were tied by familial bonds that required those with more to take care of those with less.

How does this fit with Hyde's work? In the Times article, Smith says that Hyde's thinking over the years has evolved.

Since the mid-1980s, when his work began to gain in popularity, Hyde has often been invited to speak publicly about creativity and gift exchange. Invariably, the discussions following his lectures have wound their way to a practical question: If creative work doesn’t necessarily have any market value, how is the artist to survive?

In the course of writing “The Gift,” Hyde underwent an intellectual transformation on this subject. He began the work believing there was “an irreconcilable conflict” between gift exchange and the market; the enduring (if not necessarily the happy) artist was the one who most successfully fended off commercial demands. By the time he was finished, Hyde had come to a less-dogmatic conclusion. It was still true, he believed, that the marketplace could destroy an artist’s gift, but it was equally true that the marketplace wasn’t going anywhere; it had always existed, and it always would. The key was to find a good way to reconcile the two economies.

In other words, Hyde is looking for a middle ground.

I haven't even touched on my other interest in Hyde's current work, which has to do with the the tradition of the "commons" and how it influences his thought on trademarks. The "commons" played a role in French colonial life too, slightly different than that of English colonial life. But that would be the subject of a post for another day.